Students Open Up

Radicale transparantie: hoe geef je dat vorm?

[Scroll down for English]

PDF article_radicaltransparancy_DA

Met een ogenschijnlijk onschuldige app om de meningen van studenten over docenten te peilen, stuitte DesignArbeid op heftig verzet van de Hogeschool voor de Kunsten [HKU]. Het project toont aan dat de invloed van technologie op (toekomstige) sociale relaties veel complexe kanten heeft. Steeds vaker bevragen ontwerpers, kunstenaars en architecten de maatschappelijke, sociale en culturele aspecten van beschikbare digitale data en het gebruik hiervan. Barbara Asselbergs van DesignArbeid reflecteert op hoe radicale transparantie het dagelijks leven en de ontwerppraktijk beïnvloedt.

Barbara Asselbergs

Er ontstaat een steeds groter groeiend onzichtbaar netwerk van wireless, traceerbare chips, sensoren, scanners en camera’s om ons heen. De kwaliteit en kwantiteit van de data die hiermee wordt verzameld verbetert in snel tempo. Nieuwe netwerken verzamelen deze ‘big data’ en andere netwerken combineren deze data weer tot informatie. Deze zijn vervolgens in staat iemands gezichtsuitdrukkingen, lichaamstemperatuur, hartslag, snelheid, sociale activiteiten, koopgedrag, fysieke symptomen en levensstijl (etc.) aan elkaar te koppelen. De modellen die hierdoor ontstaan kunnen het gedrag van mensen dus voorspellen, maar ook interpreteren. Vaak gaat het hierbij om vertrouwelijke informatie.

Het combineren van al deze data kan steden – en het gedrag van haar bewoners – op grote schaal transformeren. Zo is het waarschijnlijk dat er naar aanleiding van de data die we over iemand kunnen verzamelen binnen een paar jaar al maanden van te voren voorspelt kan worden of iemand een mogelijk strafbaar feit gaat plegen. Bovendien is voor het verzamelen van die informatie veelal weinig kennis vereist, noch expliciete toestemming van het publiek noodzakelijk. Maar is het wel wenselijk dat iedereen weet wat je daadwerkelijk van je buurman, je werkgever of – in het geval van dit project – je docent vindt?

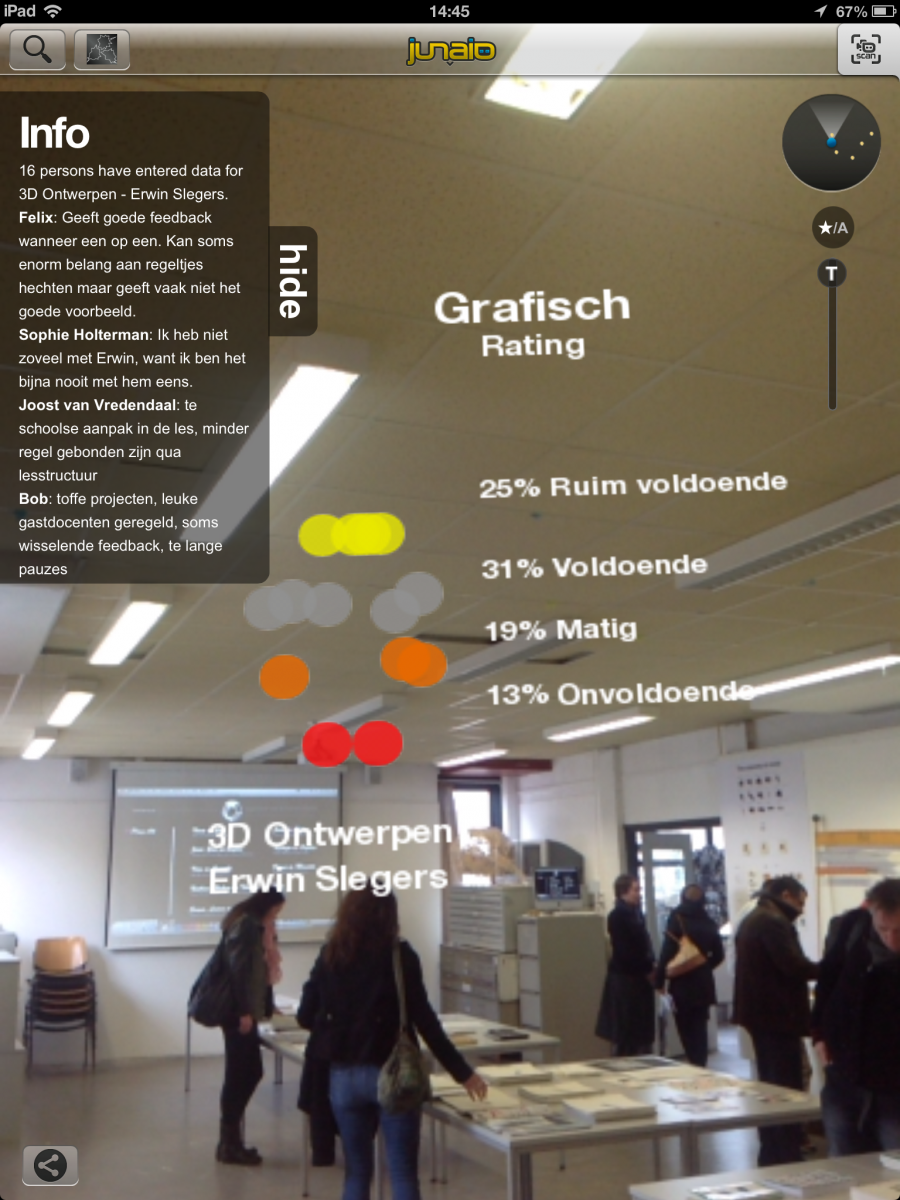

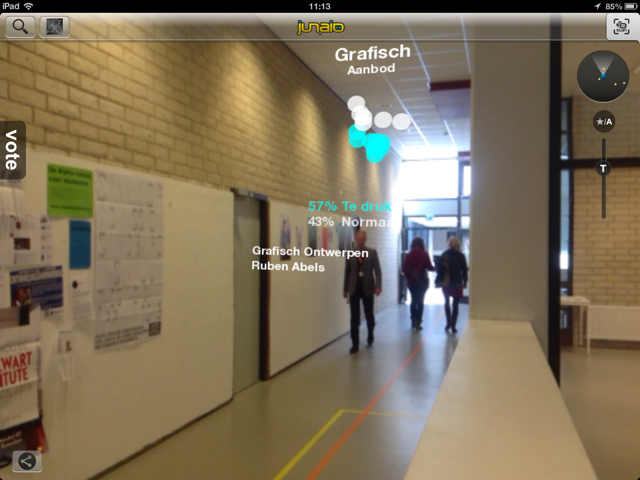

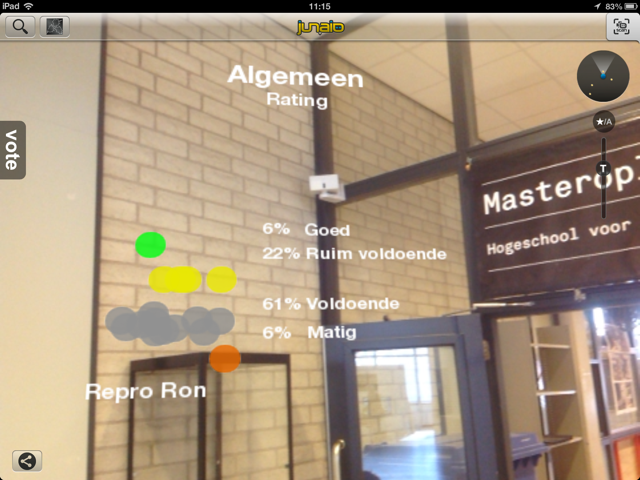

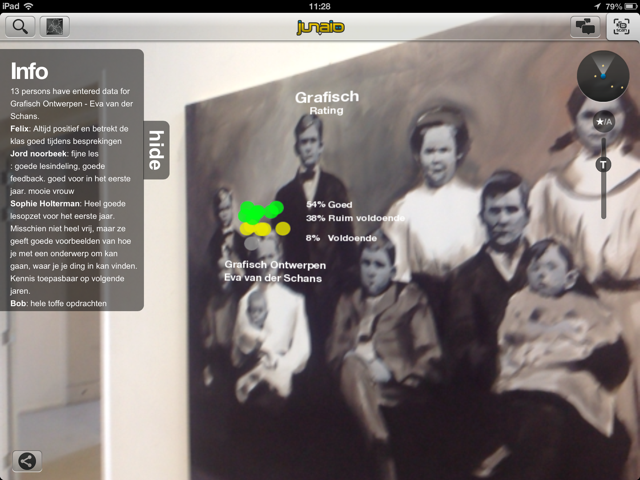

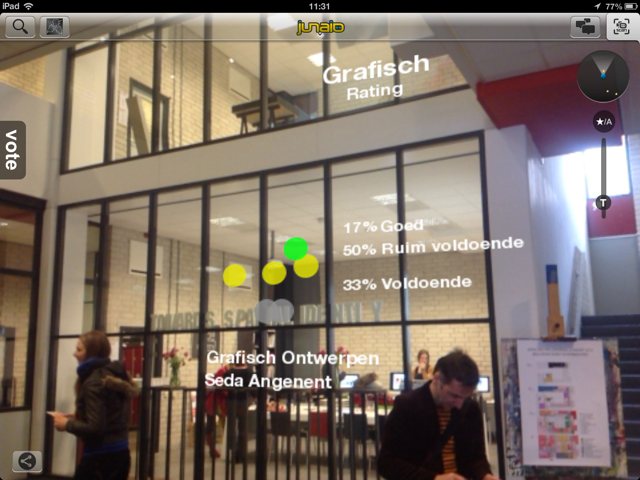

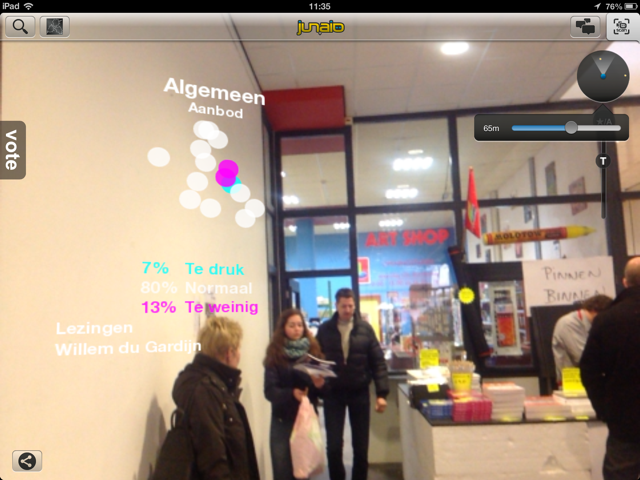

DesignArbeid presenteerde in maart 2013 “Students Open Up”. Dat is een applicatie waarin studenten van de HKU hun mening kunnen geven over het functioneren van hun docenten en de kwaliteit van de algemene faciliteiten zoals de kantine, bibliotheek en werkplaatsen. Dit deden zij niet anoniem, maar onder eigen naam. De ingevulde data zijn in een diagram zichtbaar op de afdeling waar de docenten lesgeven of daar waar de faciliteiten zich bevinden. ‘Toffe projecten’, ‘leuke gastdocenten geregeld’, ‘soms wisselende feedback’, ‘te lange pauzes’. Ruim 60 derdejaars studenten gaven hun docenten een ‘goed’, ‘ruim voldoende’, ‘matig’ of ‘onvoldoende’ met de mogelijkheid hier een korte toelichting op te geven.

Alle beoordelingen werden gekoppeld aan de locatie waar de desbetreffende docent les geeft. Niet enkel om de individuele kwaliteiten van docenten in kaart te krijgen, maar juist om de studenten en betrokkenen bewust te maken van wat het betekent dat deze informatie voor iedereen toegankelijk is. Tijdens de voorbereidingen op de interventie, waarbij de app werd gevuld door studenten van de afdeling Fashion Design, Grafisch ontwerpen, Illustration en Spatial Design, reageerden de hoofd-docenten en studenten positief op het initiatief. (Studenten van de afdeling Fotografie werkten liever niet mee, omdat dit weleens negatief zou kunnen uitpakken voor hun docenten.)

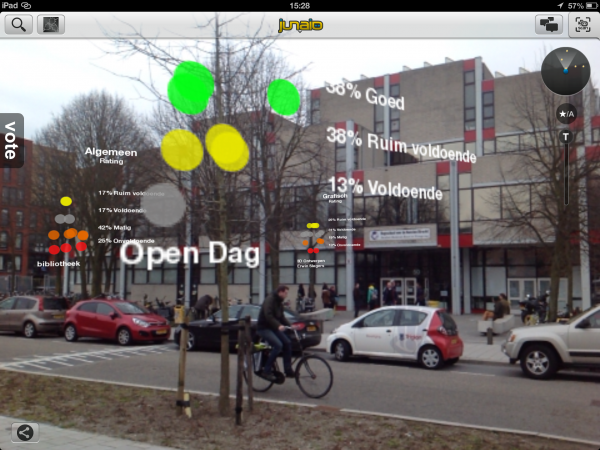

Vervolgens breidde DesignArbeid het project uit tot de open dag van de HKU op 23 maart 2013. Het is immers niet alleen een zinvol instrument om de meningen van studenten over de kwaliteit van het onderwijs in kaart te brengen. Het kan ook gebruikt worden om nieuwe studenten inzicht te geven in de meningen van studenten over de school. En dus stond tijdens de open dag een team van ontwerpers en kunstenaars met een I-pad in de hand bij de ingang en laten ze de bezoekers kennismaken met de AR app ‘Students Open Up’. De veelal jonge bezoekers installeerden de app en startten hun kennismaking met het opleidingsinstituut. Op de terugweg vroegen we hen naar de impact van de informatie die ze onderweg zijn tegengekomen en naar hun mening over de open dag.

Zou deze informatie vandaag mogelijk invloed kunnen hebben op je studiekeuze? Reacties op de eerste posts op Facebook over de open dag waren positief. De meeste toekomstige studenten vonden het een leuk idee, maar er waren ook meer inhoudelijke reacties. “Ik heb mijn keuze al gemaakt, we komen voor de opleiding en niet voor de docenten,” zeiden sommigen. Andere studenten zouden hun studiekeuze wel laten beïnvloeden door negatieve opmerkingen van studenten over hun docenten.

En toen was daar ineens een afgevaardigden van de Afdeling Communicatie. Zij was niet op de hoogte van de interventie en sommeerde DesignArbeid de interventie direct te beëindigen. Bovendien werd verzocht geen ruchtbaarheid te geven aan het project in de pers. De reden van deze heftige reactie was dat de app gecontroleerde informatieverstrekking vanuit het opleidingsinstituut op deze manier onmogelijk maakte. Naast de gereguleerde informatie van de HKU kregen de bezoekers nu immers ook een ongecontroleerd en ander verhaal gebaseerd op de mening van de huidige studenten.

De reactie is verwonderlijk, omdat experimenten als deze bij uitstek thuishoren in een omgeving van een kunstacademie waar creativiteit en vrij denken een belangrijke basis vormen. Juist deze instellingen zouden dit soort initiatieven moeten omarmen en zich ermee willen identificeren.

De schok was dat met de app een ander soort zichtbaarheid werd gecreëerd. Door de HKU van binnenuit de observeren door de ogen van de studenten verwerd het officiële publiciteitsbeleid tot slechts een van de informatiestromen die het publiek tot zijn beschikking heeft. De informatie wordt dan complexer, want die laat zich niet meer communiceren in een eenduidige, heldere taal.

Tijdens de interventie waren de studenten zich direct bewust van de consequenties van de interventie en de verantwoordelijkheid die dat met zich meebrengt. De afdeling communicatie zou daarom ook niet vanuit het belang van het instituut moeten hebben gereageerd, maar veeleer stelling genomen moeten hebben ten aanzien van de kwetsbaarheid van haar docenten en medewerkers.

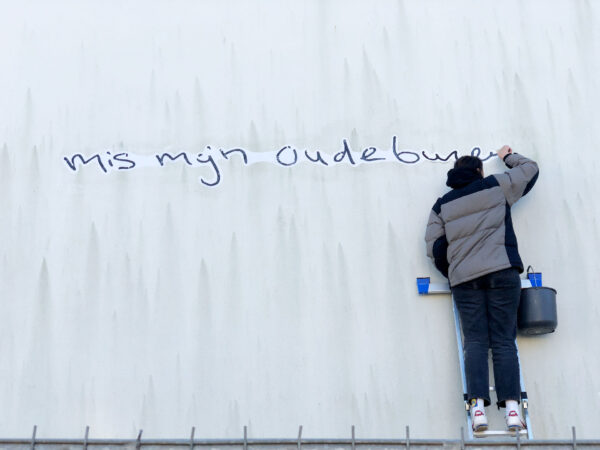

Naar aanleiding van dit en andere projecten is een stevige discussie gaande over privacy en de ethiek rondom het gebruik van data. Wat betekent deze radicale transparantie voor toekomstige omgangsvormen en het ontwerpen van nieuwe interactiemodellen? Het is immers geen optie meer om tegen of voor transparantie en openheid te zijn. Deze is er gewoon. De vraag is hoe we hier mee om wensen te gaan. Het is zaak de verstandhouding tussen de tegenpolen ‘transparantie’ en ‘geheimhouding’ te onderzoeken en vervolgens op basis daarvan strategieën en nieuwe (sociale) infrastructuren te ontwikkelen. Daar ligt een schone taak voor ontwerpers en kunstenaars om er op te reflecteren, het te visualiseren en in dit geval ook te interveniëren.

Daarbij zijn een aantal interessante aspecten. Voorafgaand aan de open dag zijn studenten klassikaal benaderd de channel persoonlijk in te vullen. Er werden meer dan 600 reviews gegeven over lessen en docenten. Studenten van de afdeling mode wilden met name anomiem meedoen, of hooguit met initiaal. Gevraagd werd in hoeverre de data de toekomstige studenten zou beïnvloeden bij hun studie keuze. Studenten van de afdeling fotografie wilden niet participieren, daar ze niet aan naming an shaming wilden doen. Zelf na uitdrukkelijk verzoek van de afdelingscoordinator, heeft deze groep niet willen meewerken aan een onderoek. Operkeijk was de erkenning van de studenten dat een vakinhoudelijk gesprek met docenten nodig zou zijn, maar dat dit tot dusver niet gevoerd was en mogelijk ook niet gevoerd zou worden.

Onderwijs

De afdeling urban design heeft besloten studenten enquetes te anomimiseren en bespreekbaar te maken en zo samen te werken naar een nieuw curriculem. Een aantal docenten heeft aangegeven deze wijze van beoordelen als zeer onprettig te ervaren, maar zijn vervolgens niet in gesprek gegaan met studenten. Een aantal docenten heeft aangegeven de output van studenten interessant te vinden, maar deze binnen het perspectief van die studenten te plaatsen; Studenten weten nog niet wat goed voor hen is. Een aantal docenten heeft het gezien als bevestiging van hun functioneren.

Radical transparency: and how to design this?

An apparently harmless app to gauge students’ opinions of their lecturers, designed by DesignArbeid, was met with fierce opposition from the art academy where it was presented. The project demonstrates that the influence of technology on (future) social relationships has many complex facets to consider. Designers, artists and architects increasingly question the civil, social and cultural aspects of available digital data and its usage. DesignArbeid’s co-owner Barbara Asselbergs reflects on the radical transparency in everyday life and how this affects design practice.

An invisible network of wireless, traceable chips, sensors, scanners and cameras is evolving around us at an exponential rate. The quality and quantity of the data collected with this network is increasing at an equally fast pace. Newly emerging networks collect so-called ‘big data’ and convert it into meaningful information. These networks are able to make connections between all kinds of physical indicators (people’s facial expressions, body temperature and heart rate) and lifestyle choices (people’s social activities and consumer behaviour). The models derived from these data cannot only predict people’s behaviour, but can also interpret it. However, this often involves confidential information. Processing all of this data can have a great impact on cities — and the behaviour of its residents. In the future these data sets from individuals could be analysed to predict the likelihood of them committing a criminal offence in the months ahead. This information can be collected without the need for specialist knowledge or any kind of explicit consent from the public. Is it, then, in any way desirable that everyone knows exactly what you think of your neighbour, your employer or, in the case of this project, your lecturer?

In March 2013 DesignArbeid presented ‘Students Open Up’, an application that allows students to share their opinions about the performance of their lecturers and the quality of general facilities like the cafeteria, the library and the work spaces. To reflect on the public nature of the data and the inability of individuals to remain anonymous, the students had to use their own name when providing feedback via the app. The data set was displayed in a graphical form in a physical location in the college rather than assigned to the individual lecturers. Responses included:‘ Cool projects’, ‘often nice guest lecturers’, ‘sometimes varying feedback’ and ‘breaks take too long’. More than 60 third-year students gave their lecturers a ‘good’, ‘satisfactory’, ‘moderate’ or ‘insufficient’ score and were able to add a brief explanation. All ratings were linked to the physical location of the relevant lecturer’s class. This was done not only to map the individual qualities of the lecturers, but primarily to make all the members of the college aware of the implications of this information being made public. In the preparation stage for the intervention, in which students from the Fashion Design, Graphic Design, Illustration and Spatial Design departments submitted data via the app, head-lecturers and students responded positively to the initiative. (Students from the Photography Department declined to participate owing to concerns that it may have negative repercussions for their lecturers).

The app is a useful tool in collecting and assessing current students’ opinions on the quality of the education provided by the institution. However, of more interest is that sharing these opinions allows prospective students to draw on the previous experiences of the existing student body to make more informed decisions regarding their future. DesignArbeid extended the project to the academy’s Open Day which took place in March 2013, to investigate this aspect further. During the

open day a team of designers and artists at the entrance of the college introduced the visitors to the ‘Students Open Up’ AR app on dedicated iPads. Of the visitors the young prospective students rather than their parents were comfortable installing the app on their phones and proceeding to the introduction to the college. On their way out they were questioned about the impact of the data from the app presented to them throughout the college and their opinions of the open day overall. Could the information from current students possibly influence prospective students’ choice of study programme? The responses to the first Facebook posts about the open day were positive. The prospective students liked the idea, and on the day itself also provided more detailed feedback. Some commented “I already made my choice, I came for the college and not for the lecturers”. Other students said they would be directly influenced by negative comments from students about their lecturers. While the event was progressing, a representative from the communication department unexpectedly stepped in. She had been unaware of the full nature of the intervention and demanded DesignArbeid to put a halt to it immediately. Furthermore, she requested that they refrain from publicising the project. The reason given for this strong response was the inability of the college to control and manage the app or the information gathered. Alongside the regulated information provided by the art academy, visitors would have access to an alternative, unedited narrative, based on the opinion of current students.

This response is remarkable given that these sorts of experiments belong in an environment such as an art academy where creativity and free-thinking experiments are a cornerstone of its mission. Indeed creative institutions should embrace these kinds of initiatives and be keen to identify themselves with them. The shock to the college authorities came from the app creating an alternative perspective. By observing the academy from the inside-out, through the eyes of the students, the official publicity policy of thecollege was reduced to just one of the flows of information the public could choose to access. The information available to the students then becomes more complex as it can no longer be presented as an unambiguous and unified narrative. When using the app to fill in their opinions, existing students indicated that they were fully aware of the consequences of the intervention, and the responsibility it entailed. Thus, the communication department should not have reacted solely with the interests of the institute itself in mind, but should have taken a stance regarding the vulnerability of its lecturers and staff.

A lively debate about privacy and the ethical impact surrounding the use of data is taking place globally. What does this radical transparency mean for individual social interactions and the design of new interaction models? In today’s world it is no longer an option to be ‘for’ or ‘against’ transparency and openness. It is simply a reality in today’s world. The question is ‘how do we want to engage with it?’. It is important to investigate the relationship between ‘transparency’ and ‘confidentiality’, and from the results of this research, develop new strategies and, perhaps even, new social structures. The challenge for designers and artists is to visualise this relationship and generate meaningful discussions in order to create solutions

to the problems raised.

The app ‘Students Open Up’ was developedby DesignArbeid in collaboration with AugmentNL. An appare ntl y harmless app to ga uge students’ opinions of their lecturers, desig ned by Desig nArbei d, was met with fierce oppositio n from the art academy where it was prese nted. The project demonstrates that the influence of te chnology on (future) social relationships has ma ny complex facets to consider . Designers, artists and architects increasingly question the civil, social and cultural aspects of available digital data and its usage . DesignArbeid’s co-owner Barbara Asselbergs reflects on the radical transparency in everyday life and how this affects design practice.

An invisible network of wireless, traceable chips, sensors, scanners and cameras is evolving around us at an exponential rate. The quality and quantity of the data collected with this network is increasing at an equally fast pace. Newly emerging networks collect so-called ‘big data’ and convert it into meaningful information. These networks are able to make connections between all kinds of physical indicators (people’s facial expressions, body temperature and heart rate) and lifestyle choices (people’s social activities and consumer

behaviour). The models derived from these data cannot only predict people’s behaviour, but can also interpret it. However, this often involves confidential information. Processing all of this data can have a great impact on cities — and the behaviour of its residents. In the future these data sets from individuals could be analysed to predict the likelihood of them committing a criminal offence in the months ahead. This information can be collected without the need for specialist knowledge or any kind of explicit consent from the public. Is it, then, in any way desirable that everyone knows exactly what you think of your neighbour, your employer or, in the case of this project, your lecturer?

In March 2013 DesignArbeid presented ‘Students Open Up’, an application that allows students to share their opinions about the performance of their lecturers and the quality of general facilities like the cafeteria, the library and the work spaces. To reflect on the public nature of the data and the inability of individuals to remain anonymous, the students had to use their own name when providing feedback via the app. The data set was displayed in a graphical form in a physical location in the college rather than assigned to the individual lecturers. Responses included:‘ Cool projects’, ‘often nice guest lecturers’, ‘sometimes varying feedback’ and ‘breaks take too long’. More than 60 third-year students gave their lecturers a ‘good’, ‘satisfactory’, ‘moderate’ or ‘insufficient’ score and were able to add a brief explanation. All ratings were linked to the physical location of the relevant lecturer’s class. This was done not only to map the individual qualities of the lecturers, but primarily to make all the members of the college aware of the implications of this information being made public. In the preparation stage for the intervention, in which students from the Fashion Design, Graphic Design, Illustration and Spatial Design departments submitted data via the app, head-lecturers and students responded positively to the initiative. (Students from the Photography Department declined to participate owing to concerns that it may have negative repercussions for their lecturers).

The app is a useful tool in collecting and assessing current students’ opinions on the quality of the education provided by the institution. However, of more interest is that sharing these opinions allows prospective students to draw on the previous experiences of the existing student body to make more informed decisions regarding their future. DesignArbeid extended the project to the academy’s Open Day which took place in March 2013, to investigate this aspect further. During the

open day a team of designers and artists at the entrance of the college introduced the visitors to the ‘Students Open Up’ AR app on dedicated iPads. Of the visitors the young prospective students rather than their parents were comfortable installing the app on their phones and proceeding to the introduction to the college. On their way out they were questioned about the impact of the data from the app presented to them throughout the college and their opinions of the open day overall. Could the information from current students possibly influence prospective students’ choice of study programme? The responses to the first Facebook posts about the open day were positive. The prospective students liked the idea, and on the day itself also provided more detailed feedback. Some commented “I already made my choice, I came for the college and not for the lecturers”. Other students said they would be directly influenced by negative comments from students about their lecturers. While the event was progressing, a representative from the communication department unexpectedly stepped in. She had been unaware of the full nature of the intervention and demanded DesignArbeid to put a halt to it immediately. Furthermore, she requested that they refrain from publicising the project. The reason given for this strong response was the inability of the college to control and manage the app or the information gathered. Alongside the regulated information provided by the art academy, visitors would have access to an alternative, unedited narrative, based on the opinion of current students.

This response is remarkable given that these sorts of experiments belong in an environment such as an art academy where creativity and free-thinking experiments are a cornerstone of its mission. Indeed creative institutions should embrace these kinds of initiatives and be keen to identify themselves with them. The shock to the college authorities came from the app creating an alternative perspective. By observing the academy from the inside-out, through the eyes of the students, the official publicity policy of thecollege was reduced to just one of the flows of information the public could choose to access. The information available to the students then becomes more complex as it can no longer be presented as an unambiguous and unified narrative. When using the app to fill in their opinions, existing students indicated that they were fully aware of the consequences of the intervention, and the responsibility it entailed. Thus, the communication department should not have reacted solely with the interests of the institute itself in mind, but should have taken a stance regarding the vulnerability of its lecturers and staff.

A lively debate about privacy and the ethical impact surrounding the use of data is taking place globally. What does this radical transparency mean for individual social interactions and the design of new interaction models? In today’s world it is no longer an option to be ‘for’ or ‘against’ transparency and openness. It is simply a reality in today’s world. The question is ‘how do we want to engage with it?’. It is important to investigate the relationship between ‘transparency’ and ‘confidentiality’, and from the results of this research, develop new strategies and, perhaps even, new social structures. The challenge for designers and artists is to visualise this relationship and generate meaningful discussions in order to create solutions

to the problems raised.

The app ‘Students Open Up’ was developedby DesignArbeid in collaboration with AugmentNL.